Οι μεταξοσκώληκες στην Αλμωπία

Τι

ήταν τα κουκούλια και γιατί είχαν τόση αξία

Τα

κουκούλια προέρχονταν από τον μεταξοσκώληκα, ένα μικρό πλάσμα που τρεφόταν αποκλειστικά με φύλλα μουριάς.

Όταν ολοκλήρωνε τον κύκλο του, δημιουργούσε το κουκούλι, από το οποίο παραγόταν

το μετάξι.

Γαϊτάνης, Α., Η Σηροτροφία στην Ελλάδα: Ιστορική αναδρομή και οικονομική σημασία, Εκδόσεις Αγροτικής Τράπεζας.

Συλλογικό Έργο, Ιστορία της Μακεδονίας: Αγροτική παραγωγή και τοπικές βιοτεχνίες, Θεσσαλονίκη.

Ντέντος, Σ. (2023). Σηροτροφία.

Αρχείο Συνεταιριστικής Τράπεζας Καρατζόβας έκδοση για τη Διεθνή Έκθεση Θεσσαλονίκης 15-30 Σεπτεμβρίου 1929.

Γενικά Αρχεία

του Κράτους (Γ.Α.Κ.) – Τοπικό Αρχείο Αλμωπίας: Στοιχεία για τη βιομηχανική δραστηριότητα.

Sericulture in Almopia: A Forgotten Heritage

There was a time when sericulture (silk farming) was an inseparable part of

daily life in Almopia. In

difficult times with limited resources, the locals turned to every possible

means to ensure their family's survival.

Life followed the rhythm of the seasons. Back then,

homes were not just places to rest; they were living workshops and social hubs.

People lived between the land, their homes, their livestock, and the mountains.

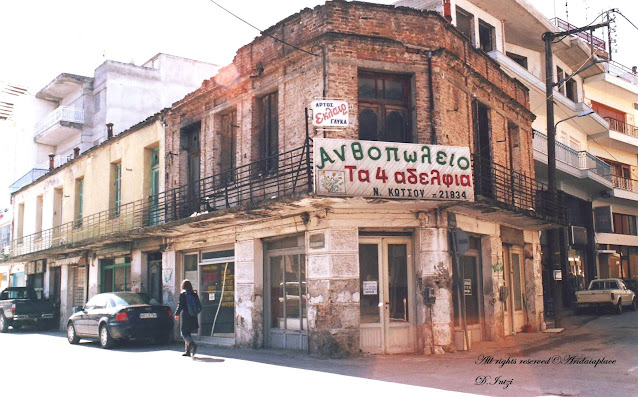

Among the daily chores, silkworm cocoons held a special place. Today, the

word is rarely heard in Aridaia,

but it once symbolized hope and a much-needed income. Even the old statue in

the town square, depicting a farming family, shows the mother holding cocoons—a

testament to their vital importance for the region.

The peak season for breeding silkworms was between May

and June, coinciding with the budding of the mulberry trees. This is exactly why Aridaia was once

filled with these trees.

Why Cocoons Were So Valuable

Cocoons were produced by silkworms, small creatures that

fed exclusively on mulberry leaves. Once their cycle was complete, they spun

the cocoon from which silk was produced.

Silkworm farming didn’t require large fields or expensive

equipment. It took place inside

the homes in clean, carefully kept rooms. It provided a vital supplementary

income for many rural families. People would build wooden or wire frames

("beds") above their own beds to house the silkworms, feeding them fresh

mulberry leaves and later entire branches. By 1929, annual production in the

area reached an impressive 178,420

okas (a traditional unit of weight). For women especially, this was a key

way to contribute to the household economy.

Eyewitness Accounts

The

Distribution of the "Seed" (Eggs)

"I remember a building across from the 1st

Nursery School of Aridaia. Every year, they would bring the silkworm eggs

there, likely through the Cooperative Bank of Karatzova. Farmers had to

pre-order their quantities. We worked there for about 20 to 25 days a year

during the hatching period. The eggs were kept in boxes, and once they hatched

in late April or early May, we placed the tiny worms into numbered boxes for

the farmers to collect. We fed them finely chopped, tender mulberry leaves and

constantly monitored the temperature, which was crucial for a successful

hatch."

Working at

the Silk Factory

"The factory was located in the 'Tsifliki' area, owned by Georgios Dizas. I remember we were exclusively women—six of us in total. Before electricity came to Aridaia, a man was also employed to manually turn the reel. The owner frequently traveled to Athens and Thessaloniki to close deals for the precious silk."

This text is based on research and oral testimonies from local residents. All rights reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)